Contents

- A Comprehensive Guide for Private Limited Companies, Branch Offices, Subsidiaries, and More.

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Practical Scenarios

- 3. Singapore Accounting Standards

- 4. Annual Filing Requirements

- 5. Goods and Services Tax (GST) Compliance

- 6. Audit Requirements

- 7. Classification of Company Expenses

- 8. Withholding Tax

- 9. Corporate Entities with Foreign Connections: The Singapore Perspective

- 10. Accounting for Foreign Entities in Singapore

- 11. Cryptocurrency Holdings and Valuation

- 12. Accounting for Non-DPT Tokens and Implications under PSA

- 13. Decentralised Autonomous Organizations (DAOs): Accounting Implications in Singapore

- 14. Comparative Analysis: Singapore Vs. Other Notable Jurisdictions

- 15. Mastering Singapore’s Accounting Requirements-Conclusion

- Appendix: Checklist for Compliance–Mastering Singapore’s Accounting Requirements

A Comprehensive Guide for Private Limited Companies, Branch Offices, Subsidiaries, and More.

1. Introduction

Singapore’s reputation as a leading business hub is well-deserved. However, this acclaim is paired with some of the world’s most rigorous accounting regulations. Mastering Singapore’s accounting requirements for private limited companies is is essential to leverage benefits, ensure compliance and avoid costly penalties. Private companies includes traditional corporate entities , branch offices, subsidiaries, and emerging new forms like decentralized autonomous organizations (DAO). This guide aims to demystify Singapore’s complex accounting landscape, offering valuable insights into statutory requirements and key considerations, particularly for entities with international connections.

2. Practical Scenarios

To illustrate the diverse challenges faced by different entities, consider the following examples:

-

Exempt Private Limited Company: ABC Tech Pte. Ltd.

A small start-up benefiting from audit exemptions but by facing challenges with GST compliance and detailed financial record-keeping.

-

Branch Office: DER Creative Singapore Branch

As a branch of a multinational corporation, this entity must navigate Singapore’s local accounting regulations while adhering to its parent company’s international reporting standards.

-

Subsidiary of a Foreign Company: FGH Holdings (Singapore) Pte. Ltd.

A European-owned subsidiary aligning its financial statements with both Singapore Financial Reporting Standards (SFRS) and IFRS for the parent company’s consolidated reports.

-

Cross-Border Transactions and Withholding Tax: IJK Solutions Pte. Ltd.

Frequently making payments to foreign vendors, this company must comply with Singapore’s withholding tax regulations and ensure accurate remittance to the Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (IRAS).

-

GST Compliance for Imported Services: LMN Global Tech Pte. Ltd.

This company imports consultancy services from international firms and must account for GST on these services, ensuring proper documentation and compliance with local GST regulations.

-

Cryptocurrency Holdings and Valuation: OPQ Digital Assets Pte. Ltd.

GHI Digital Assets Pte. Ltd., a Singapore-based cryptocurrency investment firm, faces unique accounting challenges. The company must decide whether to use the cost model or seek an active market to apply the revaluation model for its cryptocurrency holdings. Additionally, it must assess impairment when the value of the cryptocurrencies falls and ensure accurate recognition of gains and losses from crypto sales.

-

Foreign Subsidiary and Currency Conversion: RST Global Enterprises Ltd.

A Singapore-based subsidiary of a US tech company, frequently handling cryptocurrency transactions in USD. In addition to complying with Singapore Financial Reporting Standards (SFRS), the company must convert all foreign currency transactions into SGD for accurate financial reporting. JKL must also address foreign exchange gains or losses and ensure its consolidated financial statements align with both SFRS and US GAAP.

-

DAO Accounting and Regulatory Compliance: UVW DAO Pte. Ltd.

A Singapore-based decentralized autonomous organization (DAO) managing funds via smart contracts. The company must address the complexities of accounting for cryptocurrency assets and adhere to Singapore’s regulatory framework for DAOs, including compliance with Anti-Money Laundering/ Countering the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) requirements under the Payment Services Act (PSA). The DAO’s governance and financial transactions, which are conducted through blockchain technology, require meticulous documentation to ensure financial transparency and regulatory compliance.

These scenarios highlight the diverse challenges businesses in Singapore face, from GST compliance and cross-border transactions to handling complex cryptocurrency holdings. Despite these varied situations, all companies, whether they are small start-ups or subsidiaries of foreign corporations, must adhere to Singapore’s Financial Reporting Standards (SFRS). These standards, aligned with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), form the foundation of financial reporting in Singapore, ensuring consistency and transparency across entities.

Below is a breakdown of Singapore’s key accounting requirements, including annual filings, tax compliance, and audit regulations. Bear in mind the different companies from our practical scenarios as we navigate through the maze of regulations as these hypothetical examples help to put these rules in their proper context.

3. Singapore Accounting Standards

SFRS, in alignment with IFRS, forms the cornerstone of financial reporting in Singapore. Companies must adhere to these standards to ensure transparency and consistency in their financial statements.

A. SFRS vs. IFRS (A Comparative Analysis)

B. Global vs. Local Scope

C. Differences in Specific Standards

D. Reporting Deadlines and Disclosure Requirements

E. Revenue Recognition

F. Navigating the Shifting Landscape of Accounting Standards: Pre and

Post-2019 Changes in SFRS and IFRS

G. Impact of 2019 Changes to SFRS and IFRS on Accounting Operations

in Singapore

H. Current Framework

A. SFRS Vs. IFRS (A Comparative Analysis)

For international businesses expanding into Singapore, understanding the nuances between Singapore Financial Reporting Standards (SFRS) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) is crucial for ensuring compliance, maintaining financial accuracy, and optimizing operational efficiency. Although SFRS aligns broadly with IFRS, it includes local modifications tailored to Singapore’s regulatory and business context.

Significant differences arise in specific standards such as SFRS for Small Entities, which offer simplified reporting for smaller businesses, in contrast to the more complex IFRS for SMEs. Additionally, while both SFRS and IFRS require most leases to be recognized on the balance sheet, there may be variations in their implementation. SFRS also includes specific guidelines on financial instruments and derivatives that differ from IFRS. The adoption of IFRS 16 and SFRS(I) 16 in 2019 marked a major shift, requiring all but short-term and low-value leases to be recorded as Right-of-Use (ROU) assets and lease liabilities on the balance sheet. This change enhances transparency by providing a clearer view of financial obligations but introduces more complex reporting requirements.

The new standards ensure greater alignment with global practices, facilitating comparability for international investors while offering practical exemptions to ease the burden of reporting for less significant leases. Understanding these differences and the impact of the 2019 changes is essential for navigating Singapore’s accounting landscape, enabling businesses to manage taxes, make informed investment decisions, and effectively consolidate financial information across borders.

B. Global vs. Local Scope

- International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS): Adopted by 168 countries, IFRS provides a unified accounting language for global markets. Its broad application ensures consistency in financial reporting across diverse jurisdictions, facilitating easier comparison and integration of financial information.

- Singapore Financial Reporting Standards (SFRS): While SFRS is fundamentally aligned with IFRS, it is tailored to Singapore’s local context. The Singapore Accounting Standards Council (ASC) periodically updates SFRS to reflect IFRS changes while incorporating local modifications that cater to specific regulatory and business environments in Singapore.

C. Differences in Spesific Standards

- SFRS for Small Entities: One of the significant distinctions is Singapore’s introduction of the SFRS for Small Entities, a simplified version not available under IFRS. This framework reduces the complexity and reporting burden for smaller businesses by providing more straightforward reporting requirements. In contrast, IFRS does not offer a directly comparable simplified standard, although it has the IFRS for SMEs, which operates on a global scale and involves more complexity.

- Leases: Under the old SFRS 116, Singapore has adopted similar lease standards to the old IAS 17, but there may be variations in interpretation or implementation guidelines. Both frameworks aim to bring leases onto the balance sheet, but subtle differences might affect how entities manage and report leases.

- Financial Instruments: Differences also exist in the treatment of financial instruments. SFRS may have specific guidelines on derivatives and hedging transactions that differ from IFRS, affecting how these instruments are recognized and measured.

D. Reporting Deadlines and Disclosure Requirements

- IFRS: Disclosure requirements under IFRS can vary depending on the country’s interpretation, potentially leading to differences in how information is presented and reported.

- SFRS: While closely aligned with IFRS, SFRS may impose additional Singapore-specific disclosure requirements, particularly regarding corporate governance and local tax regulations, impacting how companies report and disclose financial information.

E. Revenue Recognition

- SFRS 115 vs. IFRS 15: Both standards adopt a similar revenue recognition model, but SFRS includes local regulatory nuances that can influence how and when revenue is reported. This is particularly relevant for entities involved in long-term contracts or real estate development, where specific local regulations may apply.

F. Navigating the Shifting Landscape of Accounting Standards: Pre and Post-2019 Changes in SFRS and IFRS

The evolution of financial reporting standards is crucial for global business, and Singapore has closely followed these changes to ensure alignment with international practices. In 2019, a significant transformation occurred in lease accounting under both the Singapore Financial Reporting Standards (SFRS) and the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). Here’s an overview of the changes and their implications:

I. The Pre-2019 Era: A Snapshot

Operating Leases:

Old Standards (SFRS 116 and IAS 17): Prior to 2019, operating leases were not recognized on the balance sheet under both SFRS 116 and its international counterpart IAS 17. Lease payments were recorded as expenses in the income statement as incurred.

Example: A company leasing office space for five years at $10,000 per month recorded only a monthly expense of $10,000, without any impact on the balance sheet.

Finance Leases:

Old Standards (SFRS 116 and IAS 17): Finance leases were recorded on the balance sheet, with both the leased asset and liability recognized. Depreciation and interest expenses were recorded over the lease term.

Example: Leasing machinery for five years with total payments of $100,000 required recognizing the machinery as an asset and the present value of future payments as a liability.

II. The 2019 Transformation: IFRS 116 and SFRS(I) 16

Global and Local Changes:

In 2019, both the IFRS and SFRS frameworks underwent a major overhaul with the introduction of IFRS 116 and SFRS(I) 16, respectively. The key changes were implemented to enhance transparency and consistency in financial reporting:

On-Balance-Sheet Recognition:

New Standards (IFRS 116 and SFRS(I) 16): The new standards required almost all leases to be recognized on the balance sheet, a shift from the previous approach. This involves recording a Right-of-Use (ROU) asset and a lease liability.

Example: Leasing office space for five years at $10,000 per month now requires recognizing both the present value of future lease payments as a liability and the office space as an ROU asset on the balance sheet. Payments are divided into depreciation and interest expenses.

Exemptions for Short-Term and Low-Value Leases

New Standards (IFRS 116 and SFRS(I) 16): Both IFRS 116 and SFRS(I)16 provide relief for short-term leases (12 months or less) and low-value assets, allowing these to be expensed as incurred without balance sheet recognition.

Example: Renting a photocopier for $500 per month under a six-month lease can be expensed monthly without recognizing it as an ROU asset or liability.

G. Impact of 2019 Changes to SFRS and IFRS on Accounting Operations in Singapore

Enhanced Transparency:

Impact of IFRS 116 and SFRS(I) 16: The adoption of IFRS 116 and SFRS(I) 16 has led to greater transparency by requiring most leases to be recorded on the balance sheet. This provides a clearer view of a company’s financial obligations and assets.

Impact on Financial Ratios:

Impact of IFRS 116 and SFRS(I) 16: The inclusion of lease liabilities increases reported debt levels, which can affect financial ratios such as debt-to-equity and EBITDA, influencing loan covenants and investor perceptions.

Increased Comprehensive Reporting

Transition from SFRS116 to SFRS(I)16: Previously, under SFRS 116, operating leases were off-balance-sheet, with only finance leases recognized. The new standards now require nearly all leases to be recognized, enhancing transparency and detail in financial statements.

Example: A company leasing office space for five years at $10,000 per month now records an ROU asset and a lease liability, providing a more detailed view of financial obligations.

More Onerous Reporting Requirements

Transition from IAS 17 to IFRS 116: The new standards involve complex calculations to determine the present value of lease liabilities and corresponding ROU assets, including assessing lease terms, discount rates, and future payment obligations.

Example: A five-year machinery lease with annual payments of $10,000 requires discounting these payments to their present value and recognizing them as both an asset and a liability, along with depreciation and interest expense.

Simplified Treatment for Certain Leases

Transition from SFRS116 to SFRS(I)16: While the new standards are more comprehensive, they offer simplified treatment for short-term and low-value leases, which can be expensed as incurred.

Example: Renting a photocopier for $500 per month under a six-month lease can be expensed monthly without balance sheet recognition.

Alignment with Global Standards

Transition from IAS 17 to IFRS 116: Singapore’s adoption of SFRS(I) 16 aligns with IFRS 116, ensuring that lease accounting practices are consistent with global standards. This alignment facilitates better comparability for international investors.

Example: A Singapore company using SFRS(I) 16 will present lease obligations and assets similarly to companies applying IFRS 116, aiding in cross-border financial analysis.

Summary

The introduction of IFRS 116 and SFRS(I) 16 on January 1, 2019, represents a significant shift in accounting practices for both global and Singaporean standards. These changes require comprehensive on-balance-sheet recognition of leases, enhancing transparency and consistency. While the new standards introduce more complex reporting requirements, they also provide practical relief for certain leases. By aligning with global standards, Singapore’s SFRS(I) 16 ensures that local practices are in step with international requirements, benefiting both local and international stakeholders.

H. Current Framework

SFRS(I) 16 supersedes SFRS 116 specifically for lease accounting, but the broader SFRS framework remains in place for other aspects of financial reporting. This includes ongoing SFRS standards that are not yet replaced by SFRS(I) updates, addressing various elements of financial reporting in Singapore.

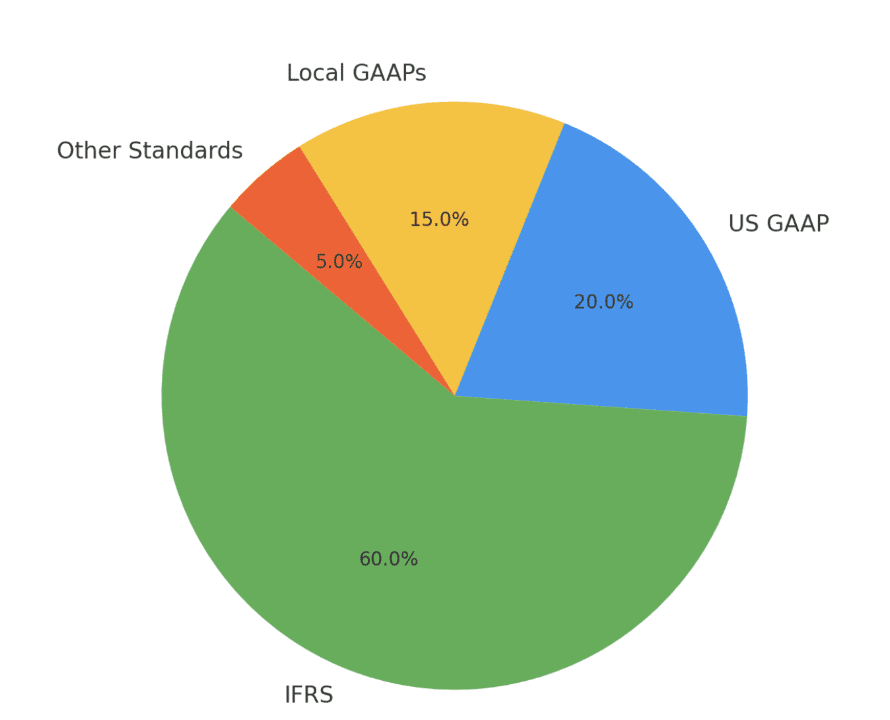

Figure 1: Global Accounting Standards Distribution (pie chart)

4. Annual Filing Requirements

A. Financial Year-End(FYE)

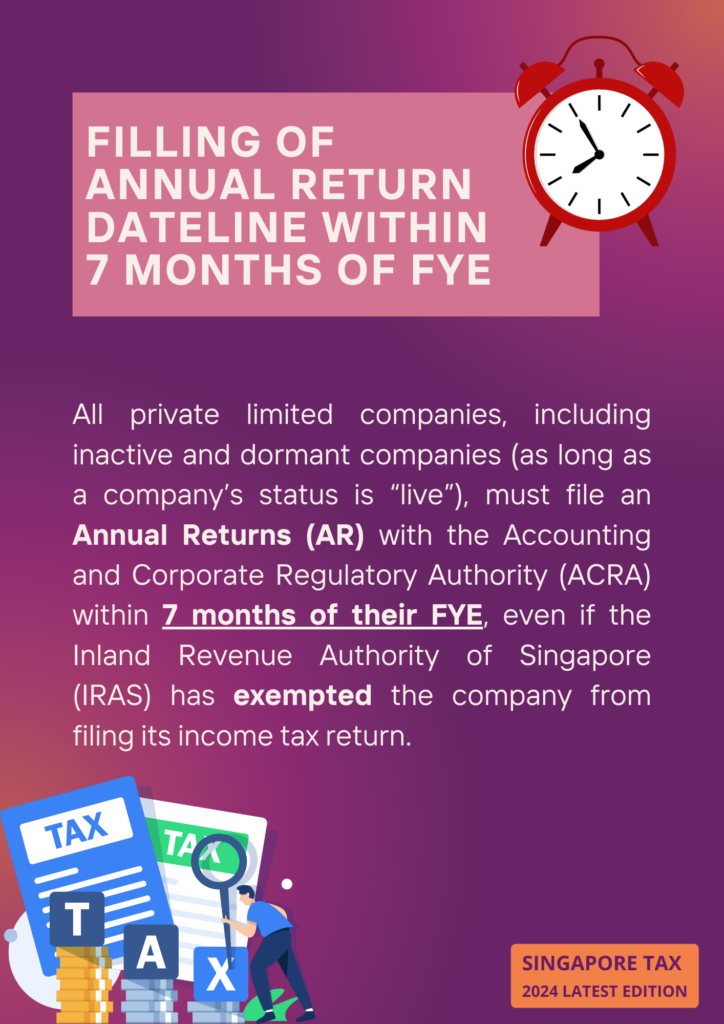

Private Limited Companies must determine their FYE and prepare annual financial statements. All private limited companies, including inactive and dormant companies (as long as a company’s status is “live”) must file Annual Returns (AR) with the Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority (ACRA) within 7 months of their FYE even if the Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (IRAS) has exempted the company from filing its income tax return.

B. XBRL Filing

Financial statements must be submitted in eXtensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL) format via ACRA’s BizFinx Preparation Tool and Multi-Upload Tool.

Figure 2: Deadline for Filing of Annual Return (infographic)

5. Goods and Services Tax (GST) Compliance

A. Registration

B. Rate Change in 2024

C. Filing and Payment

D. GST on Imports

E. GST on Exports

F. Calculation on Cross-Border Services

G. Digital Payment Token (DPT) Providers and 2024 Changes

H. Reverse Charge Mechanism

I. Filing on Digital Services & E-Commerce

J. Penalties for Non-Compliance

K. Record-Keeping and Documentation

A. GST Registration

- Threshold for Mandatory Registration: All companies, including those involved in cross-border activities like importing/exporting goods or providing services internationally, must register for GST if their annual taxable turnover exceeds SGD 1 million.

- Voluntary Registration: Companies below this threshold can voluntarily register for GST to reclaim input tax on business expenses or enhance their company profile.

- Overseas Entities: Foreign companies making taxable supplies in Singapore must register for GST, either directly or through a local agent.

B. GST Rate Change in 2024.

- From January 1, 2024, the GST rate will increase from 8% to 9%. Businesses must adjust invoicing, pricing, and GST calculations to reflect the new rate.

Transitional Rules for Transactions Spanning Rate Change

For supplies of goods or services that span the change (before and after January 1, 2024), transitional rules apply. The rate applied depends on the timing of the supply, invoice issuance, and payment receipt. Special provisions allow for charging 8% GST for goods delivered or services performed before January 1, 2024, even if invoiced after the rate change.

C. GST Filing and Payment.

Quarterly Filing Deadlines: GST-registered businesses must file their GST returns quarterly, with deadlines on the last day of January, April, July, and October. Each return covers a three-month period, and it is crucial to submit these returns on time to avoid penalties.

D. GST on Imports

- When importing goods into Singapore, GST is payable based on the value of the imported goods, which includes:

- Cost, Insurance, and Freight (CIF): The value of the goods, including any insurance costs and freight charges.

- Customs Duty and Other Charges: Any applicable customs duties or other charges imposed on the goods.

- GST is calculated as 7% of this value (rising to 9% in 2024), and businesses can typically claim this GST as input tax if they are GST-registered. To do so, proper documentation such as the import permit showing the amount of GST paid is required.

- Extension to Low-Value Goods: Effective 1 January 2023, GST is also applicable to low-value goods worth SGD 400 or less that are imported into Singapore by air or post. This includes goods purchased online from overseas retailers, aligning the tax treatment with locally purchased goods.

E. GST on Exports

The supply of goods that are exported out of Singapore is zero-rated (0% GST). While businesses are not required to charge GST on exports, they must maintain proper documentation, such as export permits and shipping documents, to substantiate the zero-rating.

F. GST on Cross-Border Services

Supplies of services to foreign clients must be assessed to determine if they are zero-rated or standard-rated under Singapore’s Place of Supply rules.

G. Digital Payment Token (DPT) Providers and 2024 Changes

The GST changes also impact Digital Payment Token (DPT) service providers. Although the primary adjustment is the GST rate itself, DPT service providers must align their GST filing, invoicing, and compliance practices to reflect the new 9% rate, which will affect any transactions related to digital payment tokens, including those involving imports or overseas services.

To stay compliant, all affected businesses, including those involved in imports or other foreign connections, must review their contracts, accounting systems, and price displays to reflect the GST rate change and apply transitional rules correctly.

Impact on Digital Payment Token (DPT) Providers and Changes to the Payment Services Act (PSA)

- The 2024 GST changes impact DPT service providers, requiring adjustments to GST practices for taxable supplies involving digital tokens, especially transactions spanning the rate change.

- Amendments to the PSA expand the scope of regulated activities to include:

- Custodial Services for DPTs: Service providers that hold digital tokens on behalf of customers must adhere to new regulatory standards.

- Facilitation of DPT Transmission and Exchange: If a business facilitates the transmission of DPTs or their exchange (even without direct involvement), these activities are now regulated under the PSA.

- Compliance and Safeguarding of Customer Assets: From October 4, 2024 (regulatory changes will take 6 months from 4 April 2024 to be fully implemented) all DPT service providers must comply with consumer protection measures, including segregating and safeguarding customer assets in trust accounts. The alignment of these activities with GST reporting is critical, particularly for cross-border DPT transactions and services

- For Importers and Exporters: The Import GST Deferment Scheme (IGDS) allows GST-registered businesses to defer GST payments on imported goods until their next GST return is due, aiding cash flow and simplifying import processes.

- Eligibility: Good compliance records, including timely GST filing and payments, are required.

H. Reverse Charge Mechanism

For Services Imported into Singapore: The Reverse Charge mechanism applies to companies unable to fully claim input tax or those partially exempt (e.g., financial institutions). The mechanism requires such businesses to account for GST on imported services as if they supplied them to themselves.

I. GST on Digital Services & E-Commerce

- Overseas Vendors and E-Commerce Platforms: Foreign companies providing digital services to Singapore customers may need to register for GST under the Overseas Vendor Registration (OVR) regime if their service value exceeds SGD 100,000 in a 12-month period.

- Local Companies and OVR: Local companies purchasing digital services from overseas may need to account for GST under reverse charge rules.

J. Penalties for Non-Compliance

- Late Filing and Payment Penalties: Failure to file GST returns or make payments on time can result in penalties, such as 5% of the outstanding tax and a SGD 200/month penalty (capped at SGD 10,000 per return).

- Additional Offenses and Penalties: Misreporting, under-declaration, or evasion of GST can lead to severe penalties, including fines up to twice the amount of tax evaded or criminal charges.

K. Record-Keeping and Documentation.

- Proper Documentation: Companies must maintain accurate records (e.g., tax invoices, import/export documents) for at least 5 years to support their GST filing.

- Audit and Compliance Checks: The Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (IRAS) conducts audits to verify compliance, and companies must provide supporting documentation for all GST transactions.

6. Audit Requirements

A. Statutory Audit

Generally required unless exempt under the ‘small company’ criteria, which applies to companies meeting at least 2 of the following 3 criteria for the immediate past two consecutive financial years:

- Total annual revenue ≤ SGD 10 million

- Total assets ≤ SGD 10 million

- Number of employees ≤ 50.

- Exceptions Due to PSA 2024 Amendments:

-

- Companies classified as Digital Payment Token (DPT) service providers are subject to mandatory audits regardless of size or exemption status. These companies must now comply with enhanced compliance measures introduced by the PSA, particularly focusing on safeguarding customer assets, Anti-Money Laundering (AML), and Countering the Financing of Terrorism (CFT) regulations.

- For DPT service providers, even if they qualify as ‘small companies,’ they must still undergo annual audits and maintain an independent audit function to assess internal controls, risk management, and AML/CFT compliance.

B. Auditor’s Report

Must comply with Singapore Standards on Auditing (SSA) and accompany the financial statements submitted to the Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority (ACRA). For DPT service providers, the auditor’s report must include an assessment of compliance with the PSA’s enhanced regulatory requirements, particularly on statutory trust obligations and safeguarding measures.

7. Classification of Company Expenses

A. Deductible vs. Non-Deductible Expenses

Deductible expenses, such as salaries and rent, are incurred for income production and can be subtracted from taxable income. Non-deductible expenses include fines and personal costs. Notably, recent case law, such as Intevac Asia Pte Ltd v. Comptroller of Income Tax [2020] SGHC 218, clarified how expenses related to R&D activities may be treated for tax purposes under Section 14D of the Singapore Income Tax Act (ITA). This landmark decision affects businesses seeking to classify and deduct R&D expenses, setting key conditions and guidelines on eligibility for deductions.

B. Capital vs. Revenue Expenditure

Capital expenditures pertain to fixed assets and are not immediately deductible; instead, they are capitalized and depreciated over time. In contrast, revenue expenditures related to daily operations are fully deductible. The case Intevac Asia Pte Ltd v. The Comptroller of Income Tax provides further context on the classification of shared business costs, particularly cost-sharing arrangements, which can influence whether such expenses are treated as capital or revenue for tax purposes.

INTEVAC ASIA PTE LTD V. COMPTROLLER OF INCOME TAX [2020] SGHC 218The Singapore High Court examined two primary tax issues: R&D expense deductions and cost-sharing arrangements:

Court Rulings:

Outcome: The High Court ultimately dismissed the taxpayer’s appeal, which had sought to claim deductions for both R&D expenses and costs shared under the cost-sharing arrangement.Highlight: The Singapore High Court reinforced a stringent approach to both R&D expense deductions and cost-sharing arrangements, denying deductions where the links to the taxpayer’s income production were not sufficiently clear or did not meet statutory requirements.Importance of case: This decision provided greater clarity on the application of tax laws to these types of expenses in Singapore, setting precedent on how such financial matters should be reported and classified. By incorporating guidelines from this legal decision, businesses can better navigate the classification of company expenses for compliance with Singapore’s evolving tax framework. |

Figure 3: Case note (table)

8. Withholding Tax

A. Applicability

Withholding tax applies to payments made to non-residents for interest, royalties, and service fees, with rates varying according to payment type and Double Taxation Agreements (DTA). Click here to see a List of countries that have entered into DTAs, Limited DTAs and Exchange of Information (EOI) Arrangements with Singapore.

B. Filing and Payment

The paying company must withhold and remit tax to IRAS by the 15th of the second month following the payment date.

C. Withholding Tax in Singapore: Why Foreign Companies Need to Understand the Principles

Grasping the principles of withholding tax is vital for effectively navigating international business operations and employment regulations. Whether it’s managing the tax obligations for an employee stationed overseas or dealing with cross-border business transactions, understanding withholding tax helps address the unique challenges and opportunities that arise in each situation. This knowledge ensures compliance with local tax laws while optimizing tax efficiency for both individuals and businesses. To illustrate these concepts in action, let’s delve into two specific hypothetical examples:

EXAMPLE 1Empty-UC Pte. Ltd., Singapore Employer Of Rajesh Sharma, Indian National Empty-UC Pte. Ltd.: A Singapore-Based Supermarket and Employer of Rajesh Sharma Rajesh Sharma: An Indian national employed by Empty-UC Pte. Ltd., who maintains financial ties to India Withholding Tax Considerations for Empty-UC Pte. Ltd: Since Rajesh maintains financial ties to India, certain tax considerations apply to his income.

Compliance in Brief: By understanding these distinctions, both Empty-UC Pte. Ltd. and Rajesh can ensure compliance with Singapore’s withholding tax rules and avoid unnecessary penalties. |

Figure 4: Example 1 of EMPTY-UC PTE. LTD. (table)

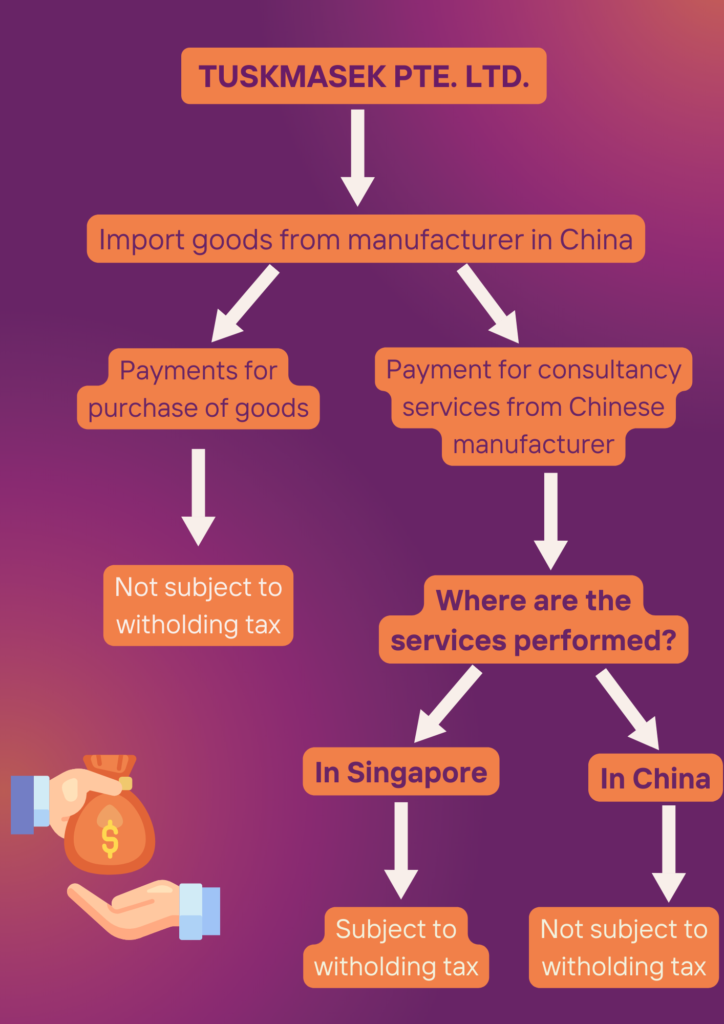

EXAMPLE 2TUSKMASEK PTE LTD A Singapore Importer Of Synthetic Medicinal Elephant Tusk From China Tuskmasek Pte Ltd.: headquartered in Singapore, is a regular importer of synthetic medicinal powdered elephant tusk from a manufacturer in China. Withholding Tax and GST Rules on Cross-Border Transactions: As a Singapore-based company, Tuskmasek is subject to both withholding tax and GST regulations for cross-border transactions.

|

Figure 5: Example 2 of TUSKMASEK PTE LTD(table)

Figure 6: Example 2 of TUSKMASEK PTE LTD(flowchart)

These examples provide clear insights into how withholding tax operates in different contexts and highlight the practical implications of international tax agreements and local regulations.

9. Corporate Entities with Foreign Connections: The Singapore Perspective

A. Transfer Pricing in Practice

B. Complete Documentation For Complying With Iras Transfer Pricing

Guidelines: Barden By The Hay (Sg) Pte. Ltd. (Company A)

C. International Considerations

When a corporate entity in Singapore has foreign connections, its accounting requirements may change. All Singapore-registered entities must comply with local regulations, including those on taxation such as Goods and Services Tax (GST) and income tax. These may impose additional obligations on companies engaged in cross-border activities.

|

KEY POINTS Overseas Income Singapore taxes only income sourced within Singapore. However, foreign income derived from outside Singapore is generally taxable in Singapore when remitted to and received in Singapore but companies may enjoy tax exemptions and concessions on such foreign income received in Singapore. Transfer Pricing Cross-border transactions must comply with Singapore’s transfer pricing guidelines, ensuring arm’s length transactions with related parties |

Figure 7: Key points to note for corporate entities with foreign connections(table)

A. Transfer Pricing in Practice

To comply with the integrated Singapore transfer pricing guidelines , companies must maintain detailed documentation supporting their pricing strategies. Here’s how Singapore’s regulations apply:

-

Arm’s Length Principle:

A Singapore company must ensure that the pricing of goods sold to related parties is comparable to market rates. For example, if an independent supplier charges $150 per unit, a significantly lower price, such as $100, could raise concerns about profit shifting.

- Required Documentation Includes:

- Benchmarking Studies: These show that the company’s prices align with industry standards.

- Financial Analysis: Detailed financial statements should validate that the company’s pricing reflects fair market value.

- Contractual Agreements: Documentation of terms, such as volume discounts, should support the pricing structure.

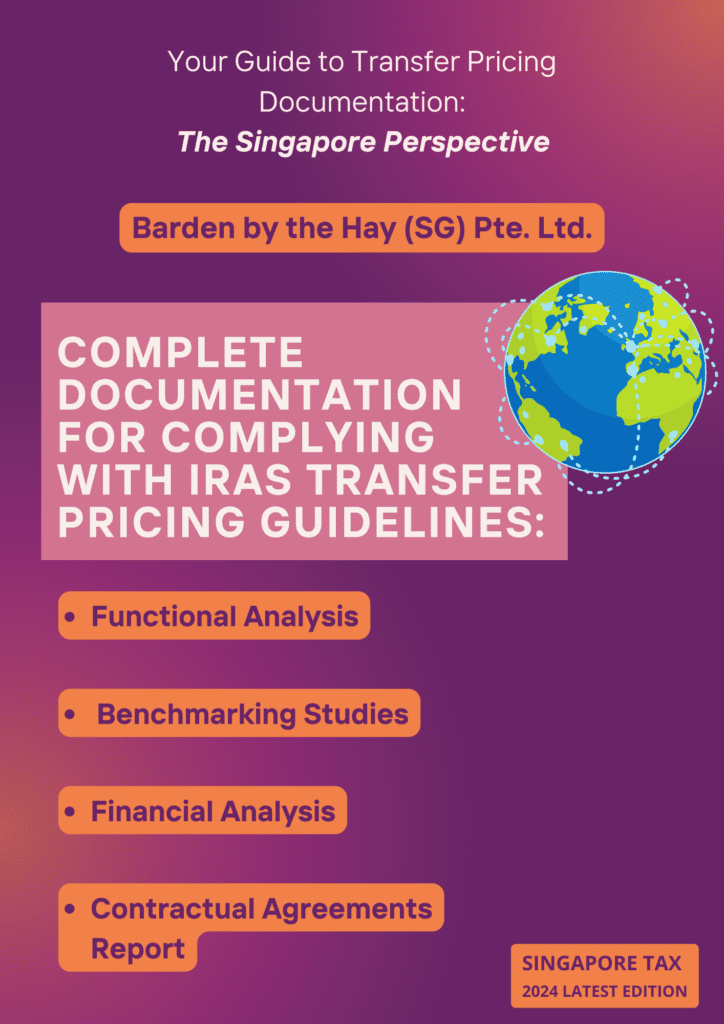

Let’s see transfer pricing in action in Singapore using the hypothetical company of Barden by the Hay (SG) Pte. Ltd.

EXAMPLEBarden By The Hay (SG) Pte. Ltd. Company Profile: Barden By The Hay (SG) Pte. Ltd. (“Company A”) is a Singapore-based manufacturer of electronic components, selling to its German subsidiary, Barden By The Hay (Germany) (“Company B”). Sales Summary (2023):

Accounting Obligations for Financial Year End 2023: Company A must ensure that the S$500 transfer price per unit complies with the arm’s length principle for the financial transactions carried out during the year. If independent suppliers charge S$550 per unit, this may trigger scrutiny from Singapore’s Inland Revenue Authority (IRAS) for potentially shifting profits to Germany.

Compliance in Brief: By preparing these documents, Company A can defend its pricing decisions and ensure compliance with Singapore’s transfer pricing regulations, reducing the risk of penalties or adjustments. |

Figure 8:Example of Transfer pricing In Action – Barden by the Hay (SG) Pte. Ltd. (table)

B. Complete Documentation For Complying With Iras Transfer Pricing Guidelines: Barden By The Hay (Sg) Pte. Ltd. (Company A)

I. Key Components of Transfer Pricing Documentation

II. IRAS Transfer Pricing Documentation Structure

III. When is Transfer Pricing Documentation Required?

IV. Timelines and Penalties

To comply with the IRAS Transfer Pricing Guidelines, Barden by the Hay (SG) Pte. Ltd. (Company A) must prepare Transfer Pricing Documentation in accordance with Singapore’s tax regulations. Here is a breakdown of the required components and best practices for compliance:

Figure 9: Key points to note for corporate entities with foreign connections(infographic)

I. Key Components of Transfer Pricing Documentation

Company Overview

- Structure, business operations, and relationships with related parties (e.g., subsidiaries, parent companies).

- Context of cross-border related-party transactions.

- Roles, risks, and assets involved in related-party transactions.

- Ensure pricing reflects an arm’s length basis (comparable to independent parties).

- Emphasis is heightened for significant cross-border transactions.

Click here to see what a Functional Analysis report would be like for Barden by the Hay (SG) Pte. Ltd.

Industry and Economic Analysis

- Overview of economic environment, industry trends, and market conditions affecting Company A.

Transfer Pricing Methodology

- Detailed description of methods used to set transfer prices (e.g., Comparable Uncontrolled Price, Cost-Plus, Resale Price Methods).

- Justification for method selection.

Benchmarking Studies

- Required for companies engaging in significant related-party transactions.

- Compare related-party transactions (e.g., S$500 transfer price per unit) to similar transactions between independent entities.

Click here for a sample benchmarking study for Barden By The Hay (SG) Pte. Ltd.,

Financial Analysis

- Comprehensive financial data supporting pricing decisions, including profit margins and key financial metrics.

- Must substantiate transfer pricing policies for cross-border transactions.

Click here to see what a Financial Analysis report would look like for Barden By the Hay (Singapore) Pte. Ltd.

- Details of contractual terms between related parties, including any adjustments like volume discounts.

- Demonstrates arm’s length pricing and ensures defensibility during audits.

Click here to see a sample Contractual agreements report for Barden by the Hay (SG) Pte. Ltd.

Compliance with Local Regulations

- Align practices with Singapore’s IRAS guidelines and OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines.

- Evidence to support non-manipulation of prices to shift profits to lower-tax jurisdictions.

II. IRAS Transfer Pricing Documentation Structure

IRAS Adopts A Three-Tiered Approach Based On OECD Guidelines:

a. Master File

-

- Overview of the MNE group’s global operations, organizational structure, and transfer pricing policies.

- Includes information on intangible assets, inter-company financing, and global tax strategies.

b. Local File

-

- Core focuses on the Singapore entity and its related-party transactions.

- Descriptions of the business, related-party transactions, functional analysis, transfer pricing methodology, and financial information.

c. Country-by-Country Reporting (CBCR)

-

- Required for MNE groups with consolidated revenue of at least S$1.125 billion.

- Provides global income allocation, taxes, and business activities by jurisdiction.

III. When is Transfer Pricing Documentation Required?

Transfer Pricing Documentation (TPD) is mandatory for entities meeting any of the following:

- Gross revenue exceeds S$10 million for the financial year.

- Related-party transactions that meet the following thresholds:

- S$15 million for purchase/sale of goods.

- S$1 million for services, royalties, rentals, or loans.

IV. Timelines and Penalties

- Documentation must be prepared before the tax filing due date.

- Must be submitted within 30 days if requested by IRAS.

- Penalties for non-compliance include fines up to S$10,000 and possible taxable income adjustments.

Note: While the term “Transfer Pricing Report” is commonly used in practice, the official term per IRAS guidelines is “Transfer Pricing Documentation.”

For compliance, Company A (Barden by the Hay (SG) Pte. Ltd.) should ensure that their Transfer Pricing Documentation is detailed, substantiated, and aligns with the arm’s length principle to avoid penalties and support its pricing decisions during audits.

The example of Barden by the Hay (SG) Pte. Ltd. highlights how the transfer pricing regulations are applied in real-world scenarios involving cross-border transactions between related entities and the importance of adhering to these regulations for fair and transparent financial practices.

📄Transfer Pricing Compliance: Do You Know What to Look Out for in Singapore?

C. International Considerations

Singapore companies must also account for the transfer pricing rules of their overseas partners, often aligned with OECD guidelines. Inconsistencies between jurisdictions could complicate compliance and result in tax disputes.

10. Accounting for Foreign Entities in Singapore

A. Key Differences Between Branch Offices And Subsidiaries

B. Profiles of Companies Suitable for Branch Offices and Subsidiaries

The accounting requirements for foreign entities depend on the corporate structure with which they choose to establish themselves in Singapore. When foreign companies establish a presence in Singapore, they have several structural options, including branch offices, subsidiaries, partnerships, or sole proprietorships, each impacting accounting obligations. While all structures require compliance with local regulations, this section will focus on the key differences between branch offices and subsidiaries, as they are the most common choices for companies seeking a more substantial presence in Singapore.

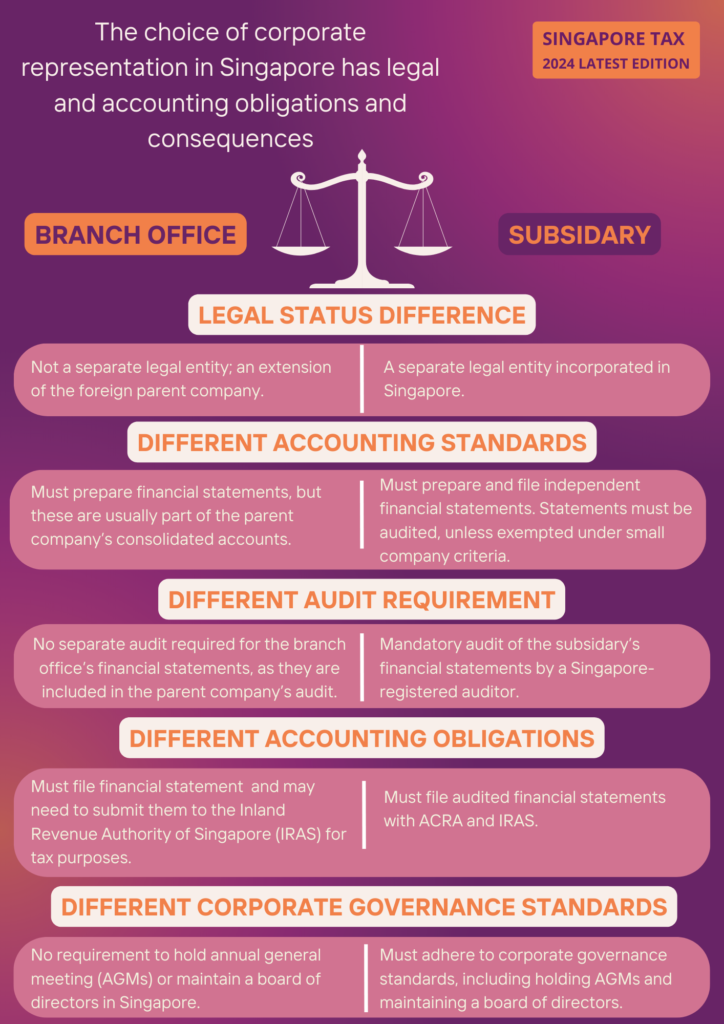

A. Key Differences Between Branch Offices And Subsidiaries

Branch office

- Legal Status: A branch is not a separate legal entity; it is considered an extension of the parent company.

- Financial Statements: Must prepare financial statements in compliance with Singapore Financial Reporting Standards (SFRS), but these are not filed separately with the Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority (ACRA).

- Tax and GST Compliance: Must comply with local tax regulations, including GST, and file returns with the Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (IRAS).

- Audit Requirements: Generally, a separate audit is not required, as the branch’s financial activities are consolidated with the parent company’s audited accounts.

Subsidiary

- Legal Status: A subsidiary is a distinct legal entity incorporated in Singapore.

- Financial Statements: Must prepare and file its own financial statements in accordance with SFRS and consolidate them with the parent company’s reports under IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards).

- Audit Requirements: Subject to statutory audits unless exempted as a “small company.”

- Corporate Governance: Must adhere to stricter corporate governance requirements, including appointing a local director and company secretary.

Figure 10:Branch office vs. Subsidiary (infographic)

Summary

Both branch offices and subsidiaries operate under different regulatory frameworks. Branch offices are extensions of the parent company and face less stringent regulations, whereas subsidiaries, as independent entities, must comply with more rigorous requirements. Understanding these differences is critical for making informed business decisions.

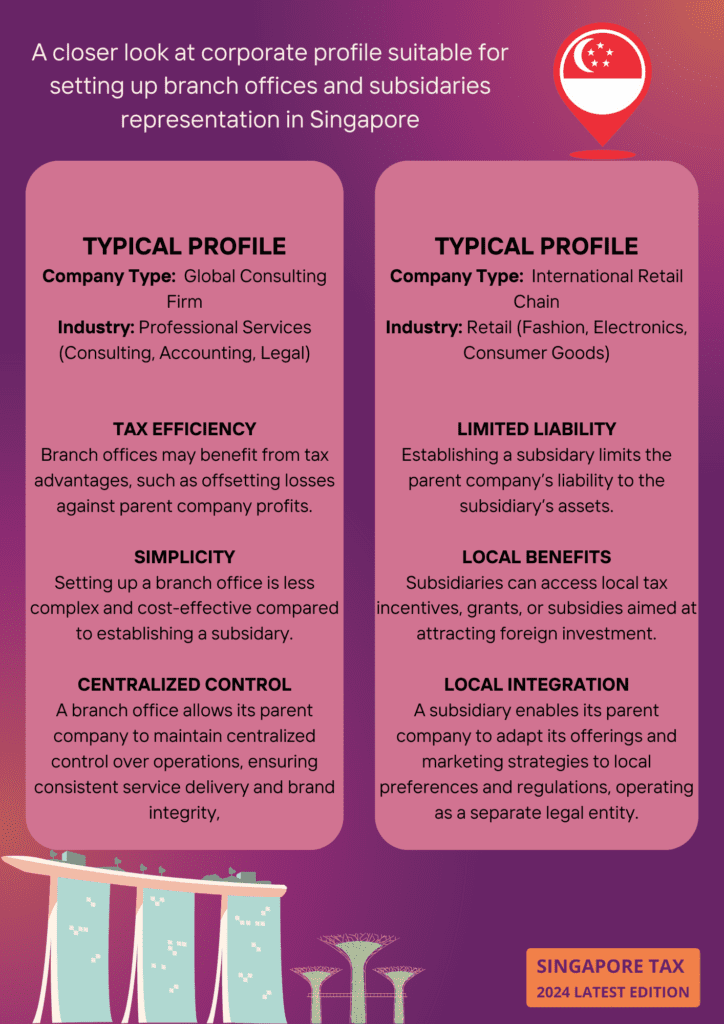

B. Profiles of Companies Suitable for Branch Offices and Subsidiaries

Profile Suitable for a Branch Office

- Company Type: Global Consulting Firm

- Industry: Professional Services (Consulting, Accounting, Legal)

Why a Branch Office?

- Centralized Control: A branch office allows its parent company to maintain centralized control over operations, ensuring consistent service delivery and brand integrity.

- Tax Efficiency: Branch offices may benefit from tax advantages, such as offsetting losses against parent company profits.

- Simplicity: Setting up a branch office is less complex and cost-effective compared to establishing a subsidiary.

Profile Suitable for a Subsidiary

- Company Type: International Retail Chain

- Industry: Retail (Fashion, Electronics, Consumer Goods)

Why a Subsidiary?

- Local Integration: A subsidiary enables its parent company to adapt its offerings and marketing strategies to local preferences and regulations, operating as a separate legal entity.

- Limited Liability: Establishing a subsidiary limits the parent company’s liability to the subsidiary’s assets.

- Local Benefits: Subsidiaries can access local tax incentives, grants, or subsidies aimed at attracting foreign investment..

Summary

- Branch Office: Best suited for companies needing centralized control and uniform service delivery, with fewer regulatory requirements and potential tax benefits.

- Subsidiary: Ideal for companies seeking a strong local presence, operational flexibility, limited liability, and potential local incentives.

Figure 11: Profiles for Branch office vs.Subsidiary (infographic)

The decision between a branch office and a subsidiary hinges on a company’s strategic goals, operational needs, and the regulatory environment in Singapore. Understanding the accounting requirements for each structure is further complicated by the differences between Singapore Financial Reporting Standards (SFRS) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). While SFRS broadly aligns with IFRS, it includes local modifications tailored to Singapore’s regulatory framework, making it crucial for businesses to grasp these distinctions to ensure compliance and optimize financial reporting.

11. Cryptocurrency Holdings and Valuation

A. Business Activities Involving Cryptocurrencies: The Singapore Perspective

B. Accounting Standards for Cryptocurrencies: The Singapore Perspective

C. Considerations for Companies with Foreign Connections

D. Requirements for Companies dealing with Cryptocurrencies

E. Business Activities Involving Cryptocurrencies

F. Regulatory And Compliance Considerations for Companies carrying out Business Activities Involving Cryptocurrencies

G. Cryptocurrency Regulation under the Payment Services Act

H. Crucial Distinction Under The PSA

I. Cryptocurrencies Under Other SG Regulations

J. Changes to Small Company Exemptions and Audits for Cryptocurrency Businesses in Singapore

K. Key Details Of Changes In 2024 To The Regulatory Requirements For Dpt Service Providers

L. Impact of 2024 Summer Changes to PSA on Financial Reporting

M. 2024 Key DPT Regulatory Changes

A. Business Activities Involving Cryptocurrencies: The Singapore Perspective

Companies in Singapore engaging in cryptocurrency-related business activities face distinct accounting challenges in addition to the traditional accounting standards applied to private limited companies, subsidiaries, and branch offices. Under Singapore Financial Reporting Standards (SFRS), cryptocurrencies are classified as intangible assets, typically accounted for using the cost model. However, revaluation options are limited due to the volatile nature of cryptocurrency markets. With regulatory frameworks evolving—such as the stricter auditing and compliance measures under the Payment Services Act (PSA)—businesses must navigate both accounting and regulatory complexities in Singapore’s dynamic financial landscape.

📃Click here for the key features of the unique Singapore’s Payment Services Act.

B. Accounting Standards for Cryptocurrencies: The Singapore Perspective

In Singapore, the accounting treatment of cryptocurrencies is primarily guided by the following standards:

- SFRS 38 (Intangible Assets): Cryptocurrencies are generally treated as intangible assets.

- SFRS 36 (Impairment of Assets): Impairment rules apply when the value of cryptocurrencies declines and is unlikely to recover.

- SFRS 2 (Inventories): If cryptocurrencies are held for sale or trading purposes, they may be treated as inventory.

|

EXAMPLE Marina Bay Fence Pte. Ltd. (SG Cryptocurrency Investment Company) Scenario: Marina Bay Fence Pte. Ltd purchased 10 Bitcoins for S$500,000 in January. By December, the value had dropped to S$400,000, and no recovery is expected. Initial Recognition (January):

Year-End Impairment (December):

|

Figure 12: Profiles for Branch office vs. Subsidiary (Table)

C. Accounting Considerations for Companies with Foreign Connections

For companies with foreign operations, additional complexities arise:

- Currency Conversion: Transactions must be converted into Singapore Dollars under SFRS 21.

- Tax Treatment: Foreign subsidiaries may face different tax treatment, subject to double taxation agreements.

- IFRS Compliance: Foreign branches or subsidiaries may need to reconcile local accounting standards with SFRS for consolidated financial statements.

|

EXAMPLE Let’s say Marina Bay Fence Pte. Ltd from our earlier example has a foreign subsidiary in the US that buys and trades cryptocurrency. Here’s how accounting requirements could change:

|

Figure 13: Example of MARINA BAY FENCE PTE. LTD (Table)

Furthermore, companies handling cryptocurrencies must comply with a range of accounting requirements influenced by the classification of the cryptocurrency and the nature of their business activities. This classification subsequently determines which specific legislations apply to them.

D. Accounting Requirements for Companies dealing with Cryptocurrencies

The applicable legislation significantly influences the accounting requirements that companies dealing with cryptocurrencies must adhere to. This determination largely depends on several factors:

- The Role of Cryptocurrency: How cryptocurrency functions within the corporate structure.

- Nature of Business Activities: The specific business activities involving cryptocurrencies.

- Regulatory Classification: Whether the cryptocurrency is classified as a Digital Payment Token (DPT) under the Payment Services Act (PSA), thereby subjecting it to regulatory oversight.

This section explores the accounting obligations for companies in Singapore that actively engage with cryptocurrencies, whether as their core business activity or as part of a wider strategic framework.

E. Business Activities Involving Cryptocurrencies

The accounting requirements these companies must comply with depends on the role that cryptocurrency plays in their business activities.

|

Common Types of Business Activities Involving Cryptocurrencies

|

Figure 14: Types of Business Activities Involving Cryptocurrencies(Table)

F. Regulatory And Compliance Considerations for Companies carrying out Business Activities Involving Cryptocurrencies

The Singapore Government adopts a cautious approach to regulating cryptocurrencies. While recognizing their economic and social potential, the aim is to balance fostering innovation with proportionate risk management, particularly concerning consumer protection and Anti-Money Laundering/ Counter-Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT).

Cryptocurrencies are not legally treated as equivalent to money in Singapore. Depending on their characteristics, they may be classified as a capital markets product (like securities), e-money, or a Digital Payment Token (DPT) under the Payment Services Act (PSA)—or they may remain unregulated if they are used solely for utility purposes. The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), Singapore’s central bank, actively regulates the DPT space and is engaged in various projects, like “Project Ubin,” “Project Orchid,” and “Project Guardian,” exploring blockchain, asset tokenization, and central bank digital currencies (CBDCs).

G. Cryptocurrency Regulation under the Payment Services Act

Under the PSA, cryptocurrencies can fall into two categories:

I. Regulated Cryptocurrencies: These are DPTs that meet the PSA’s criteria—acting as mediums of exchange, stores of value, or units of account. Service providers dealing with DPTs must comply with licensing, AML, and CFT regulations. A DPT service may involve either dealing in DPTs (e.g., buying or selling them for money or other DPTs) or facilitating their exchange (e.g., operating a DPT Exch).

II. Unregulated Cryptocurrencies: These are tokens that do not fit the PSA’s criteria as DPTs or any other regulated payment service. Though they might still be legal for use or trade, they are not subject to the PSA’s regulatory framework. A key example includes tokens used for specific, limited purposes, like customer loyalty points or in-game assets that cannot be converted back to money.

In essence, the PSA categorizes cryptocurrencies as either DPTs (regulated) or Non-DPTs (unregulated). If a cryptocurrency meets the DPT criteria, it falls under PSA regulations and requires

compliance with licensing and AML/CFT obligations.

|

Key DPT Service Provider Licenses under the PSA Entities providing payment services related to DPTs are required to obtain a payment license. There are two main licenses:

License applicants must meet eligibility criteria, including capital requirements and having at least one executive director who is a Singapore citizen or Permanent Resident. |

Figure 15:Key DPT Service Provider Licenses under the PSA(Table)

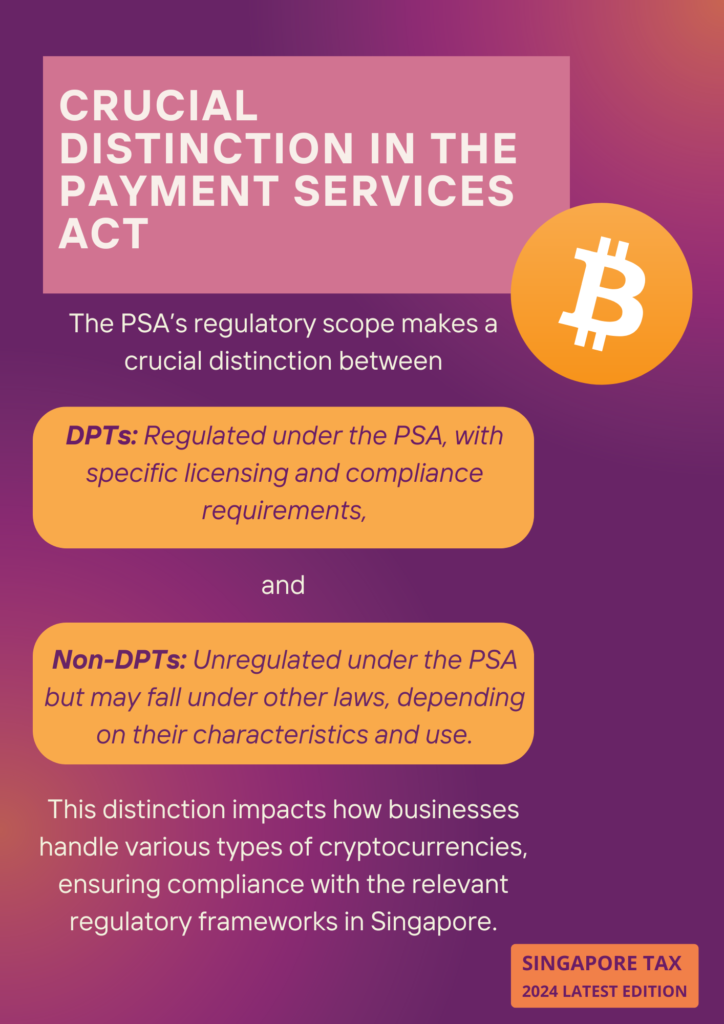

H. Crucial Distinction Under The PSA

The PSA’s regulatory scope makes a crucial distinction between:

- DPTs: Regulated under the PSA, with specific licensing and compliance requirements.

- Non-DPTs: Unregulated under the PSA but may fall under other laws, depending on their characteristics and use.

- This distinction impacts how businesses handle various types of cryptocurrencies, ensuring compliance with the relevant regulatory frameworks in Singapore.

Figure 16:Crucial distinction in the PSA (infographics)

I. Cryptocurrencies Under Other SG Regulations

If a cryptocurrency exhibits features of securities or capital markets products, it might also be regulated under the Securities and Futures Act (SFA). In such cases, additional licensing or prospectus requirements apply. Furthermore, if a cryptocurrency is asset-backed, it may be subject to the Commodity Trading Act.

Securities and Futures Act (SFA)

Companies involved in cryptocurrency activities are subject to additional regulatory requirements in Singapore, particularly under the PSA and the Securities and Futures Act (SFA).These include:

- AML/CFT Compliance: Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism measures must be adhered to, with regular audits to ensure compliance.

- Audit Requirements: Cryptocurrency-related assets must be audited annually, in line with Singapore’s audit standards.

- Licensing Requirements: In addition, cryptocurrency exchanges and primary platforms for digital token issuance must obtain a Capital Market Services (CMS) license, contingent upon meeting the financial requirements set by the MAS. This requirement clarifies the distinction between firms focused on blockchain innovation and those engaged in market-making activities within the cryptocurrency space.

Notice PSN02 (or the “Crypto Travel Rule”)

Furthermore, to combat money laundering and terrorist financing risks, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has issued Notice PSN02, commonly known as the Crypto Travel Rule. This notice outlines comprehensive Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Combating the Financing of Terrorism (CFT) guidelines specifically for Digital Payment Token (DPT) service providers. The notice and its subsequent amendments require DPT service providers to perform customer due diligence, report suspicious transactions, and implement robust transaction monitoring processes to detect potential misuse.

Under Notice PSN02, DPT service providers must adhere to strict AML and CFT regulations. These regulations mandate the maintenance of detailed and accurate transaction records to facilitate monitoring and reporting of any suspicious activities. Regular audits of compliance policies are also crucial, ensuring that these policies are effectively applied and updated in line with evolving regulatory expectations.

Guidelines PS-G03 issued on 19 September 2024

These are guidelines on the provision of consumer protection safeguards by digital payment token service providers. One of the guidelines has made it mandatory for DPT service providers to provide thorough training for their employees. This training equips staff with the necessary skills to identify and report suspicious transactions or activities, promoting a culture of compliance and vigilance within the organization. Emphasizing employee education is vital, as front-line personnel are often the first line of defense against potential illicit activities.

Notice PSN01

In addition to the requirements set forth in MAS Notice PSN02, the newly revised Notice PSN01 mandates that capital markets intermediaries, including Digital Payment Token (DPT) service providers, establish internal controls and procedures for reporting suspicious activities and incidents of fraud. This notice emphasizes the importance of having robust mechanisms in place to detect and escalate any irregularities, thereby enhancing the overall compliance framework for cryptocurrency firms. Auditors are tasked with evaluating these reporting processes to ensure adherence to regulatory expectations, further solidifying the commitment of DPT service providers to combat money laundering and protect customer assets.

Consequently, accounting firms working with cryptocurrency companies must expand their focus beyond traditional financial reporting. They need to incorporate these AML/CFT regulatory requirements into their auditing processes, ensuring that their clients not only meet financial standards but also maintain robust measures against money laundering and terrorist financing. This dual approach enhances the credibility and reliability of cryptocurrency businesses while safeguarding them from potential legal and regulatory repercussions.

The MAS FinTech Regulatory Sandboxin Cryptocurrency VenturesAs part of its balancing act between circumspection and innovation, the MAS FinTech Regulatory Sandbox offers a unique opportunity for cryptocurrency companies to test their business models in a controlled environment. Key aspects include:

|

Figure 17:The MAS FinTech Regulatory Sandbox(Table)

Summary

Cryptocurrency businesses in Singapore must navigate a unique set of accounting and regulatory challenges, from valuation and impairment to compliance with evolving frameworks such as the PSA. Properly classifying and accounting for cryptocurrency holdings is essential to maintain compliance and ensure accurate financial reporting.

KEY POINTS FOR CRYPTO-RELATED BUSINESS ACTIVITIES IN SINGAPOREIn Singapore, companies dealing with cryptocurrency are subject to a range of accounting requirements, influenced by how cryptocurrency is classified and the activities related to it. Here’s a summary of key points: I. Classification of Cryptocurrencies

II. Revenue Recognition

III. Fair Value Accounting

IV. Tax Treatment

V. Regulatory ReportingCompanies dealing with cryptocurrencies must comply with the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS )regulations under the Payment Services Act (PSA).

VI. Audit Requirements

|

Figure 18: Key Points For Crypto-Related Business Activities In SingaporeTable)

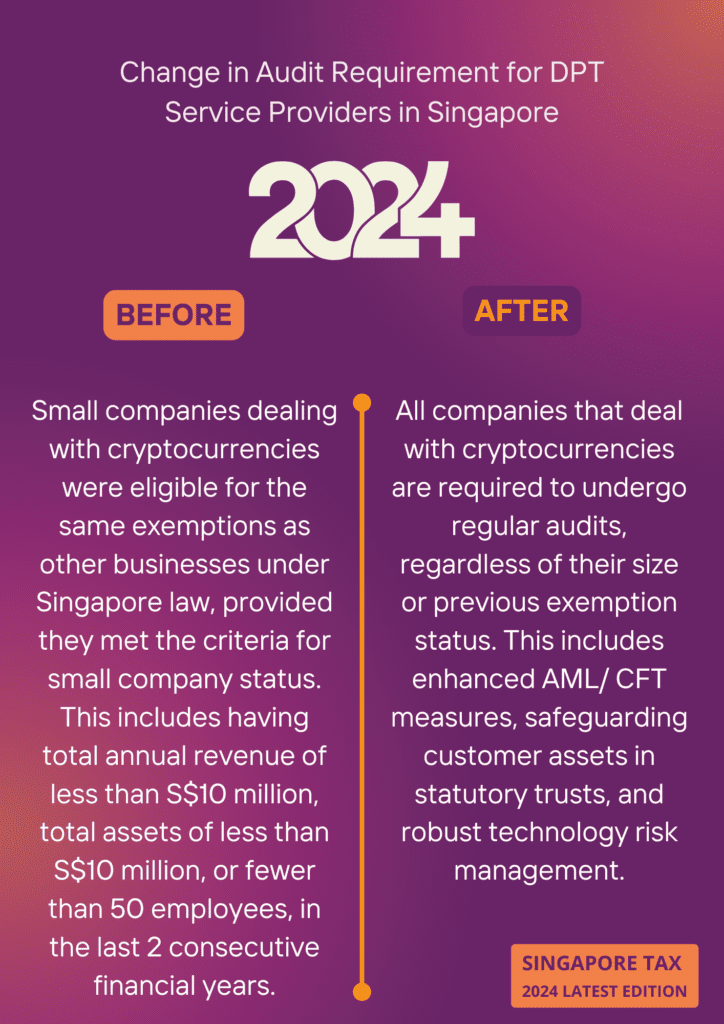

J. Key Details Of Changes In 2024 To The Regulatory Requirements For Dpt Service Providers

As of April 2024, significant regulatory changes have been introduced for companies dealing with cryptocurrencies in Singapore, particularly those classified as Digital Payment Token (DPT) service providers. These changes aim to strengthen consumer protection and enhance regulatory oversight. While small companies previously enjoyed certain audit exemptions, the amendments to the Payment Services Act (PSA) now require stricter compliance measures, including mandatory audits for all DPT service providers. The following section outlines the previous framework for small company exemptions and details the new requirements post-2024.

-

Before 2024:

Previously, small companies dealing with cryptocurrencies were eligible for the same exemptions as other businesses under Singapore law, provided they met the criteria for small company status. This included having total annual revenue of less than S$10 million, total assets of less than S$10 million, or fewer than 50 employees.

-

After April 2024:

Following the regulatory changes introduced in April 2024, all companies that deal with cryptocurrencies are required to undergo regular audits, regardless of their size or previous exemption status. This includes enhanced AML/CFT measures, safeguarding customer assets in statutory trusts, and robust technology risk management.

Figure 20: Summary of Changes in PSA in 2024 (infographics)

-

After April 2024: Mandatory Audits for Cryptocurrency Companies

Following the regulatory changes introduced in April 2024, all companies dealing with cryptocurrencies, particularly Digital Payment Token (DPT) service providers, regardless of their size or previous exemption status.

However, Digital Payment Token (DPT) service providers—such as cryptocurrency exchanges, custodial wallet providers, and payment processors—face stricter and more direct regulatory requirements under these amendments. The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) implemented these changes to enhance consumer protection and ensure compliance with international standards.

Key regulatory updates include:

- Enhanced AML/CFT Measures: Companies must comply with stricter Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) regulations, requiring thorough audits of AML/CFT policies and controls. As of August 2024, the Anti-Money Laundering and Other Matters Bill has been passed to strengthen AML/CFT regulations. This includes requiring thorough audits of policies and controls related to AML/CFT for cryptocurrency service providers, ensuring greater compliance and oversight.

- Safeguarding of Customer Assets: DPT service providers are now required to maintain customer assets in statutory trusts, with additional internal controls to ensure the proper safeguarding of these assets. Auditors must assess compliance with these statutory trust obligations, ensuring that customer assets are appropriately segregated and protected from misuse.

- Robust Technology Risk Management: DPT service providers must have effective risk management measures in place for technologies used in handling and securing cryptocurrencies. The audit must evaluate the company’s technology risk management policies, including cybersecurity protocols, transaction security, and data protection. As of February 6, 2024, MAS issued the revised Notice PSN05 on Technology Risk Management, expanding its scope to include Digital Payment Token Service Providers (DPTSPs). This change is in response to global IT disruptions that affected customers of DPT service providers, highlighting the need for these providers to maintain high system availability and protect customer information.

Important Requirements For DPT Service Providers Under The Revised Guidelines:

-

- Identifying Critical Systems: DPTSPs must establish frameworks to identify their critical systems.

- Protecting Customer Information: IT controls should be in place to prevent unauthorized access to customer data.

- Maintaining System Availability: DPTSPs should ensure that critical systems have a maximum unscheduled downtime of no more than four hours within a 12-month period.

- Incident Reporting: DPTSPs must notify MAS within one hour of discovering a severe IT security incident and submit a root cause analysis report within 14 days.

- Specific Audit Report Requirements: Under the updated regulatory framework, all DPT service providers must maintain an independent audit function to regularly assess their internal controls, compliance measures, statutory trust obligations, and asset management. The auditor’s report must explicitly include an assessment of the company’s adherence to PSA requirements, particularly concerning the safeguarding of customer assets and the implementation of statutory trusts.

- The requirement for Digital Payment Token (DPT) service providers to maintain customer assets in statutory trusts, along with the associated audit obligations, is part of the amendments to the Payment Services Act (PSA). These changes are aimed at enhancing customer asset protection and ensuring that DPT providers adhere to strict regulatory standards. Specifically, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) is focused on ensuring compliance with rigorous Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Combating the Financing of Terrorism (CFT) guidelines. As of now, DPT service providers must not only implement robust internal controls to safeguard customer assets but also have independent audits to verify adherence to these statutory trust obligations. This includes maintaining detailed records and regular assessments to ensure compliance with MAS requirements.

K. Impact of 2024 Summer Changes to PSA on Financial Reporting

The new MAS regulations in 2024 do not alter existing accounting standards under SFRS or IFRS, but they impose additional compliance costs on companies involved in DPT services. These costs, which must be reflected in financial reporting, encompass compliance with statutory safeguarding measures, risk management, and AML/CFT requirements.

I. Audit Functions & Compliance Costs:

While the new regulations do not modify accounting standards under SFRS or IFRS, compliance costs for DPT service providers have increased. These include new statutory trust requirements to safeguard customer assets, which must be segregated and held in trust, ensuring they are not mixed with the service provider’s assets. This change is meant to improve investor protection and is accompanied by daily asset reconciliation and maintaining proper records.

II. AML/CFT & Statutory Trust Compliance:

The ongoing obligations under the AML/CFT framework (PSN01 and PSN02) have been revised to apply to all scoped-in payment services effective from April 2024. The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has also added the requirement for DPT service providers to submit an external auditor attestation on their compliance with AML/CFT within a set timeline.

III. Technology Risk Management & Safeguarding Costs:

In addition to technology risk management expenses, there are new requirements for DPT service providers to provide monthly statements of account to customers and ensure robust risk management controls for customer assets. However, lending or staking of DPTs for retail customers has been restricted for better consumer protection.

L. 2024 Key DPT Regulatory Changes

|

2024 Key DPT Regulatory Changes: Compliance, Audits & Consumer Protection A Summary

While audits are now mandatory for DPT service providers, it’s crucial to note that these requirements apply regardless of the size of the company, aiming to enhance transparency and safeguard customer assets. This means full audits covering financial controls, AML/CFT compliance, and safeguarding of assets are required.

The emphasis on compliance with AML/CFT measures has increased, particularly due to revised guidelines (PSN01 and PSN02) to align with global standards and MAS’s “group policy” requirements. Additionally, DPT service providers must implement statutory trust measures for consumer asset protection, with assets segregated and held in trust.

Auditors are expected to assess compliance with the Payment Services Act (PSA) regulations, including statutory trust requirements and the safeguarding of assets. Auditors must provide an attestation on the company’s business activities and compliance status.

All DPT service providers, irrespective of their size or scale, are subject to regular audits and adherence to MAS regulations. These audits encompass enhanced regulatory requirements, such as safeguarding consumer assets and ensuring appropriate risk management protocols. |

Figure 21: Summary of Changes in PSA in 2024 (Table)

12. Accounting for Non-DPT Tokens and Implications under PSA

A. Introduction

B. Definition of Non-DPT Tokens

C. Accounting Treatment of Non-DPT Tokens

D. Valuation Approaches

E. Regulatory Considerations under PSA

F. Implications of Non-DPT Tokens on Financial Reporting

G. Tax Considerations for Non-DPT Tokens

H. Challenges and Considerations

A. Introduction.

The rapid evolution of the cryptocurrency landscape has given rise to various types of digital tokens, including those classified as non-Digital Payment Tokens (non-DPTs). Understanding the accounting treatment of these tokens is crucial for businesses operating in Singapore, particularly in light of the regulatory framework established by the Payment Services Act (PSA). This section explores the classification, accounting standards, regulatory considerations, and implications for non-DPT tokens, providing a comprehensive overview for companies engaged in cryptocurrency-related activities.

B. Definition of Non-DPT Tokens

Non-DPT tokens refer to digital representations of value that do not qualify as Digital Payment Tokens under the PSA. These tokens often serve specific functions within ecosystems rather than acting as a medium of exchange. Examples include:

- Utility Tokens: Used for accessing a service or product (e.g., Starbucks Rewards Points).

- In-Game Currencies: Coins or credits restricted to specific gaming environments (e.g., V-Bucks in Fortnite).

- Asset-Backed Tokens: Digital representations of ownership in real-world assets (e.g., real estate).

- Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs): Unique digital assets representing ownership of singular items (e.g., digital art).

- E-Money Tokens: Tokens backed 1-to-1 by fiat currency but not intended for general use as payment tokens (e.g., stablecoins).

- Private Network Tokens: Tokens used within closed blockchain networks for specific applications.

C. Accounting Treatment of Non-DPT Tokens

The accounting treatment of non-DPT tokens primarily falls under SFRS. Depending on their characteristics, these tokens can be classified as:

- Intangible Assets: Utility tokens and NFTs are generally recognized as intangible assets under SFRS 38. They should be measured at cost and subsequently tested for impairment.

- Inventory: In-game currencies, if held for resale, may be classified as inventory under SFRS 2, applying the cost model unless an active market exists, allowing for revaluation.

- Financial Instruments: Certain asset-backed tokens may qualify as financial instruments under SFRS 109, subjecting them to specific recognition and measurement criteria.

D. Valuation Approaches

Non-DPT tokens are typically accounted for using the cost model. However, if a token’s fair value can be determined, entities may consider using the revaluation model. Impairment testing is essential, particularly for intangible assets, ensuring that values reflect realistic market conditions.

E. Regulatory Considerations under PSA

Companies dealing with non-DPT tokens must navigate the regulatory landscape set forth by the PSA. Although non-DPT tokens may not fall under the strict definitions of DPTs, businesses may still encounter various compliance obligations, including:

- AML/CFT Compliance: Businesses must implement Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Countering the Financing of Terrorism (CFT) measures, regardless of whether they deal in DPTs.

- Audit Requirements: Companies may be subject to audit requirements, especially if they operate under a business model that involves the exchange or management of non-DPT tokens.

Licensing Considerations: While many non-DPT activities may not require a PSA license, businesses offering ancillary services or engaging in larger-scale operations should assess their licensing needs carefully. This ensures compliance with MAS regulations and mitigates potential legal risks.

F. Implications of Non-DPT Tokens on Financial Reporting

The financial reporting implications for businesses dealing with non-DPT tokens are multifaceted. Companies must ensure accurate recognition and reporting of these tokens in their financial statements:

- Recognition and Reporting: Non-DPT tokens should be reported in accordance with their classification (e.g., intangible assets, inventory). Companies must document the valuation basis and any impairments recognized during reporting periods.

- Example Scenarios:

- A company trading utility tokens may recognize revenue based on the fair value at the time of the transaction, consistent with SFRS 115.

- In-game currencies held for resale would be treated as inventory, requiring careful tracking of cost and potential revaluation based on market conditions.

G. Tax Considerations for Non-DPT Tokens

The tax implications of dealing with non-DPT tokens can vary significantly based on their classification and usage:

- Tax Treatment of Income: Income derived from transactions involving non-DPT tokens, such as utility tokens or NFTs, is generally taxable if it constitutes part of the company’s business activities.

- GST Treatment: Companies must assess whether their services involving non-DPT tokens are taxable or exempt from Goods and Services Tax (GST), with careful consideration of turnover thresholds.

H. Challenges and Considerations

Businesses face unique challenges in accounting for non-DPT tokens, including:

- Complexity in Classification: Determining the appropriate classification for various tokens can be complex, necessitating robust internal controls and policies.

- Regulatory Compliance: Navigating regulatory obligations can be daunting, especially for startups with limited resources. Ensuring compliance with both MAS guidelines and accounting standards is crucial.

Summary

Understanding the accounting and regulatory implications of non-DPT tokens is essential for businesses in Singapore’s evolving cryptocurrency landscape. With proper classification, compliance with the PSA, and adherence to SFRS, companies can navigate the complexities of managing non-DPT tokens while positioning themselves for growth in the digital economy.

13. Decentralised Autonomous Organizations (DAOs): Accounting Implications in Singapore

Decentralised Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) operate without centralized leadership, governed by smart contracts on blockchain networks. In Singapore, DAOs present unique challenges in both accounting and regulatory compliance due to their decentralized nature and reliance on cryptocurrencies. Let’s explore how DAOs fit within Singapore’s regulatory and accounting frameworks.

A. Legal Status and Structure Challenges for DAOs

DAOs, as decentralized entities, do not easily fit into traditional corporate structures, which raises challenges for legal status and accountability. They may fall under the category of a collective investment scheme under Singapore’s Securities and Futures Act (SFA), especially if property or assets are involved with potential returns. A solution is to structure the DAO as a Company Limited by Guarantee (CLG) to achieve compliance, hold assets legally, and provide liability protection for its members. This structure can also simplify accounting and reporting, but it somewhat diminishes the pure decentralized vision of a DAO.

B. Accounting for Contributions and Tax Implications

Currently, there is no specific authoritative guidance in Singapore for accounting contributions to or receipt from a DAO. However, DAOs can be considered taxable entities, and cryptocurrency transactions are subject to taxation based on where the sale or service occurs. This means that participants may need to track transactions for potential capital gains or losses. If a DAO distributes funds as grants or payments, these must be valued in local currency (e.g., SGD or USD) at the time of transfer, which impacts revenue recognition and reporting.

C. Financial Transparency and Trust Challenges

Since DAOs are inherently decentralized, achieving financial transparency can be difficult. The use of smart contracts facilitates transparent record-keeping, yet the lack of central management presents challenges in ensuring proper documentation for compliance with Singapore’s Payment Services Act (PSA). Establishing accounting practices for DAOs requires a balance between transparent blockchain operations and accurate reporting for regulatory adherence.

D. DAO as a Digital Payment Token (DPT) Provider

If a DAO is involved in activities like issuing tokens, facilitating exchanges, or offering custodial services, it may be classified as a DPT provider under the PSA. This classification imposes obligations, such as obtaining an MAS license and implementing AML/CFT measures. The decentralized and pseudonymous nature of DAOs makes these compliance requirements challenging, particularly for Know Your Customer (KYC) processes.

E. Technology and Regulatory Framework Gaps

Due to the decentralized nature of DAOs, it is unclear how to assign responsibilities for regulatory compliance, which increases challenges in financial reporting and accountability. This lack of clarity highlights the need for evolving structures or systems to help DAOs align with Singapore legal frameworks. The lack of a clear accounting structure creates a skill gap and potential trust issues, particularly when it comes to financial decision-making and the alignment of member interests.

F. Accounting for Token Valuation and Impairment

DAOs must consider how to fairly value tokens and how these are reflected in financial statements. The absence of clear accounting standards for DAOs necessitates the use of traditional models, like the cost or revaluation models under SFRS 38. Revenue recognition, impairment calculations, and capital gain/loss adjustments must be made in line with SFRS 115 and other relevant standards.

G. Future Directions: Adapting to Regulatory Developments

Given the evolving nature of DAOs and their rising popularity, future legal developments may provide specific guidelines for DAOs on governance, liability, and cross-border activities. Legal experts suggest exploring alternative structures, such as CLGs (a Public Company Limited by Guarantee), that balance the decentralized nature of DAOs with practical compliance requirements in Singapore.

Summary

While DAOs provide a decentralized and transparent approach to organizational governance, they face practical and regulatory challenges in Singapore. From compliance with the PSA to meeting financial reporting requirements, DAOs need to proactively manage their structure, transactions, and governance to align with Singaporean laws and accounting standards.

14. Comparative Analysis: Singapore Vs. Other Notable Jurisdictions

A. Global Spectrum of Accounting Standards: From Strict to Lax

B. How does Singapore compare

C. Structural and Practical Barriers to Full IFRS Adoption in Singapore

D. Dynamic, Interpretive, and Human Factors in IFRS Integrational in Singapore

A. Global Spectrum of Accounting Standards: From Strict to Lax